The Curious Boy

Young Antonie discovering the power of lenses

In 1644, in the small Dutch city of Delft, a twelve-year-old boy named Antonie van Leeuwenhoek pressed his face close to a piece of glass. Most people would see just a simple lensA curved piece of glass or other transparent material that bends light to make objects appear larger or clearer, but Antonie saw something magical. Through this curved glass, the threads of his shirt appeared as thick as ropes, and the wings of a fly looked like delicate windows with tiny veins running through them.

"How is this possible?" young Antonie whispered to himself. The lens seemed to open a door to a world that had always been there but invisible to the naked eye. He didn't know it yet, but this moment of wonder would change science forever.

Antonie wasn't born into a family of scientists or scholars. His father sold baskets, and his mother came from a family of brewers. There were no universities in his future, no fancy laboratories waiting for him. But what Antonie had was something more powerful than any degree: an unstoppable curiosity about the world around him.

The Lens Maker's Apprentice

As Antonie grew older, he became an apprentice to a cloth merchant. His job was to examine fabrics and judge their quality. To do this well, merchants used magnifyingMaking something appear larger than it really is, usually by using a lens or mirror glasses to count the threads in each piece of cloth. The finer the threads and the more tightly woven, the better the fabric.

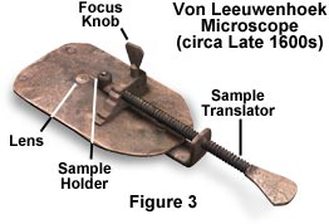

Replica of one of van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes

But Antonie wasn't satisfied with the magnifying glasses available to him. They made things bigger, yes, but the images were often blurry. He thought, "What if I could make a better lens? What if I could see things even more clearly?"

So Antonie began teaching himself to grind and polish lenses. This was incredibly difficult work. He would take a small glass bead and carefully shape it, polishing it for hours and hours until it was perfectly smooth and perfectly curved. Most lens makers would have been satisfied with a lens that magnifiedEnlarged or made something appear bigger objects ten or twenty times their actual size. But Antonie was different. He kept experimenting, kept polishing, kept trying to do better.

The Incredible Microscope

By the time he was forty-one years old, in 1673, Antonie had created something remarkable. His microscopesInstruments that use lenses to make very small objects appear much larger so they can be studied weren't like the microscopes we use today. They were tiny—about the size of your thumb—and made of brass or silver. Each one had a single, very special lens that Antonie had ground himself.

These lenses were extraordinary. While other microscopes of the time could magnify things 20 or 30 times, Antonie's best microscopes could magnify objects up to 270 times! To understand how amazing this is, imagine taking something the size of a pinpoint and making it appear as large as a baseball.

Antonie made hundreds of these microscopes during his lifetime. For each thing he wanted to study—a drop of water, a bee's stinger, a grain of sand—he would make a special microscope and mount the specimenA sample or example of something, especially one used for scientific study or testing permanently in it. He was like an artist who never reused his canvases, making sure each observation got the perfect tool for viewing.

The Invisible World Revealed

One day in 1674, Antonie decided to look at a drop of lake water under one of his powerful microscopes. What he saw made him gasp in amazement.

Lake water under a microscope - the invisible world Antonie discovered

The water wasn't empty—it was teeming with life! Tiny creatures swam and wiggled and spun through the water. They were so small that a thousand of them could fit on the head of a pin, yet through Antonie's microscope, he could see them clearly. Some were round, some were oval, some had little tails that whipped back and forth to help them swim.

🔬 What Antonie Saw:

"I now saw very plainly that these were little living animalculesA historical term for microscopic organisms; literally means "tiny animals". They were swimming in the water, and they were round like eggs. There were thousands of them in just one drop of water!"

Antonie had discovered microorganismsLiving things that are so small they can only be seen with a microscope, such as bacteria and tiny creatures—living things so tiny that no one had ever seen them before. These weren't just interesting shapes or patterns; these were actual living creatures eating, moving, and reproducing in a world invisible to the human eye.

He looked at everything he could find. Scrapings from his teeth revealed even more creatures. Rainwater, river water, even the water in flower vases—all of it was filled with microscopic life. The world, Antonie realized, was far more crowded with living things than anyone had ever imagined.

Sharing the Discovery

Antonie knew he had found something important, but would anyone believe him? After all, he was just a cloth merchant from a small Dutch town. He had never been to university. He didn't even know Latin, the language that scientists used to communicate with each other at that time.

One of Antonie's actual letters to the Royal Society, written in Dutch

Gathering his courage, Antonie wrote a letter to the Royal Society of London, the most important scientific organization in the world. In his letter, written in Dutch, he described the tiny creatures he had seen. He tried to explain how they moved, how they looked, how they seemed to be alive.

At first, the scientists in London were skeptical. Living things too small to see? It sounded impossible! But Antonie kept writing letters—eventually sending over 300 letters during his lifetime—each one describing new observationsThings that are seen and noted carefully, especially for scientific study. He described blood cells for the first time. He discovered bacteria. He observed the life cycle of tiny insects. He looked at muscle fibers and nerve cells.

Eventually, the Royal Society sent trusted scientists to visit Antonie in Delft. When they looked through his microscopes and saw the tiny creatures for themselves, they were astounded. Antonie was telling the truth! The Society published his letters and made him a member—an incredible honor for someone with no formal scientific training.

A Legacy of Wonder

Antonie van Leeuwenhoek continued his microscopic explorations for over fifty years. Famous people from all over Europe came to Delft to look through his microscopes. He showed them wonders they had never imagined—the compound eye of an insect, the circulation of blood in the tail of a tadpole, the structure of wood and plants.

When Antonie died in 1723 at the age of ninety, he had opened the door to an entirely new branch of science. Today, we call him the "Father of MicrobiologyThe branch of science that studies microscopic organisms like bacteria, viruses, and other tiny living things"—the study of tiny living things. His work led to our understanding of germs and disease, to the development of antibiotics, to countless discoveries about how life works at its smallest levels.

But perhaps most importantly, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek showed us that you don't need fancy credentials or expensive equipment to make groundbreaking discoveries. What you need is curiosity, patience, careful observation, and the courage to look at the world in new ways.

The next time you look at a drop of water, remember: it contains an entire invisible universe, waiting to be explored. All you need is the curiosity to look closer and the wonder to appreciate what you find.